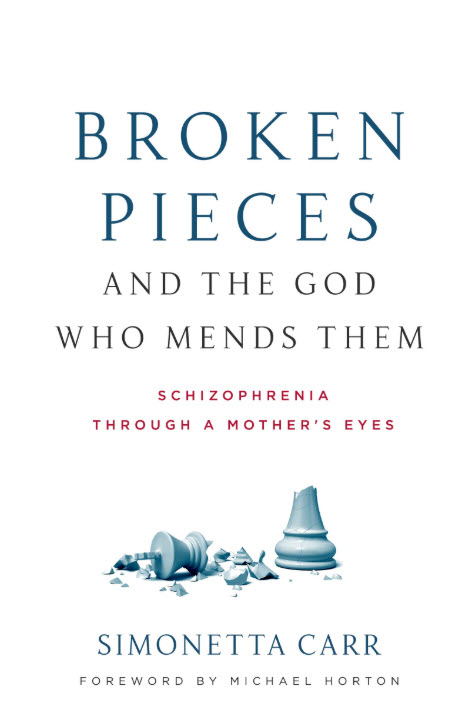

Author Simonetta Carr, foreword Michael Horton

A Critical Review

In Broken Pieces and the God Who Mends Them, Christian author Simonetta Carr tells the story of her son whose relentless pursuit of mind-altering drugs led to substance-abuse psychosis and his eventual death at twenty years of age. The book of 368 pages was published in Febuary 2019 by Presbyterian & Reformed Publishing, with a foreword written by theologian Michael Horton, Professor of Theology and Apologetics at Westminster Seminary.

Broken Pieces describes little or no discipline from the parents, but details the author’s search for help in a myriad of mental health experts. Simonetta Carr states in the introduction, “I am hoping to encourage other parents and relatives of people living with schizophrenia and possibly with other mental illnesses – regardless of their religious convictions- as they keep reading, finding resources, and seeking help”. (14, italics mine)

She concludes the book with truth: “Keep hoping and praying. Whatever the outcome, we have a good and powerful God, who has done all things well.” (351) However, it seems unrelated to all the previous pages.

Part 1: Through the Unknown: Jonathan’s Story

This first section causes the reader to repeatedly ask, “Why don’t you just say No!” or “Stop that” or “Move out!” By her own inadvertent revelation, Carr shows herself to be what the secular world would term an ‘enabler’.

She begins the story with a family photo from the oldest brother’s wedding. The author-mother describes Jonathan’s “observant brown eyes, long eyelashes, perceptive humor” and “his genius” combined with “deep understanding” (19). She goes on to state that her son “saw himself as very intelligent” and that he expressed this intelligence in a poem entitled I Am. Although the poem describes only Jonathan with no mention of the great I AM (Exodus 3:14), Carr prints the entire poem in the book as an example of Jonathan’s “depth of thought… when he was thirteen.” (20, 21).

He failed “two of his four courses” at University of California Merced and was “asked to leave” at age eighteen. There is no suggestion that she or her husband sought to discover what happened at the University. Carr simply says, “…so he told us.” (18, 19) She describes herself as comforted when Jonathan decides to stay home from college. After all, “I am Italian. I think all my kids should stay home forever.” (25)

When the parents of Jonathan’s girlfriend report his regular use of marijuana to Pastor Brown, Carr finds it devastating. Jonathan refuses to repent though the elders ban him from the Lord’s Table “as a system of pastoral correction” (26). No effort to discover what other mind-altering substances were taken is mentioned. Instead, Carr hugs him, sits by him, stares into the distance, and tells her son that “if this were the sixties, we could wear some colorful bands on our heads and look perfectly groovy.” (29) Jonathan bathes little and “stays up all night and sleeps during the day” (while continuing to wear “his struggling dreadlocks” to which the young man has “a strong emotional attachment”), so Carr decides to “give him some space” (30).

Only when taken to “a life counselor” is Jonathan asked about his use of other mind-altering substances. He admits to ‘mushrooms’; the counselor advises exercise and creative painting. Jonathan says, “I could have come up with [that].” and Carr decides she has “antagonized [her] son enough” (34)

In one of the few times Carr’s husband Tom (the source of the medical insurance) is mentioned, he “acts calmly and pragmatically” in taking Jonathan to the general practitioner and on to the psychiatrist. She notes that “…most of the time, Tom lets me follow my instincts.” The young man is given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and Tom picks up the prescription for Risperidone. (35). The mother says, “[This] gives me hope. Jonathan has some pills to take.”(37)

When she learns that Jonathan purchased marijuana with the money she gave him for food, she explains it as trying to “self-medicate with whatever he can find at home” (48). In a similar manner, she decides that his refusal to take his prescribed medications is “another part of the illness called anosognosia” (a deficit of self-awareness resulting from brain damage). (49)

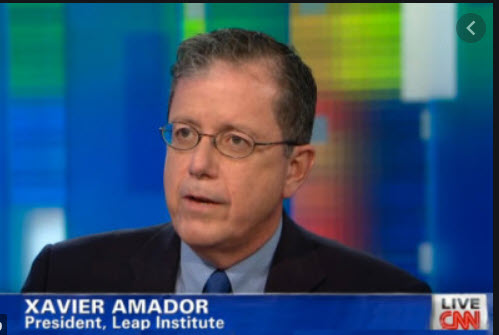

She turns to TV personality Xavier Amador, an internationally renowned clinical psychologist, who advises she build a nonjudgmental relationship with Jonathan so that he feels respected, not judged. She tries to reflect back Jonathan’s illusions, apologize for her opinion, acknowledge her infallibility, and agree to work with him. (51) Things get worse, and “many people” advise giving Jonathan “an ultimatum.” She “can’t do it” and “can’t live knowing that he is homeless.” Instead, she is thankful when Jonathan “goes to his room and curls up under his blanket.” (55)

When he “starts to use foul language” and refuses to go to church, Carr finds it “hard to believe…Jonathan had always been our brightest son.” (59) She then turns to Andrew Solomon, a psychologist in a same-sex marriage where both males have produced children with female friends. After reading his Far from the Tree, Carr is impressed that “Jonathan fits [Solomon’s] description to a T”(62). She gives her son “another laptop—the third in a row—hoping that he will be more responsible with it [having] already lifted any restriction.”(65)

Baffled by the young man’s worsening behavior, Carr describes how Jonathan was “nourished with whole grains” and was “delivered in a natural way, making sure the lights were dim to avoid any distress as we welcomed him into the world.” (69) The parents decide to “put a lock on his door so he will not feel the need to barricade himself.” (75) When the Psychiatric Emergency Response Team finally takes Jonathan to the psychiatric hospital, Carr prays that God “will heal him through the scientific means he has provided.”(82) Though waiting on these scientific means, she writes, “What is schizophrenia, really? Maybe scientists will find out one day.”(84)

Carr concludes that her son “has a very advanced case of schizophrenia” and is “gravely disabled.” (88) She asks Jonathan “for forgiveness while understanding that [she] may never receive it.” (89) As the medication list goes from Valium and Haldol to Zyprexa, Ativan, Trazodone, Prolixin, and a muscle relaxant, Carr concludes that “the doctors must know what they are doing.” (90). She sends Jonathan an e-mail saying, “I just want to thank you for taking your meds. They will help you so much in the future to lead a happier life.” (100)

She turns to “one of [her] friends, an acupuncturist with a PhD in psychology” who advises healthy food. (101) She learns that “with a marijuana card, [Jonathan] can call a dispensary…and they deliver [the marijuana] to the house.” (104) Her “friend Jay who runs a compounding pharmacy” reassures her that the marijuana “is not dangerous [but] will magnify the soothing effect of …Ativan or Trazodone.” (105)

After Jonathan takes an overdose of Ativan, the social worker “suggests [that Carr] should manage his medications and ask for [Jonathan’s] approval.” (111) Carr decides he should get a job after reading Richard Warner’s The Environment of Schizophrenia describing how political, economic, and labor market forces shape psychiatric treatment philosophy (117). With paychecks from Home Depot, “he can buy [marijuana] with no problem” (125). Jonathan tells her, “I talked to the pastor. It’s okay [to use marijuana].” Pastor Brown tells Carr that the elders are “having patience because of Jonathan’s condition.” (126)

Carr prays “that the doctors can find the right balance of medications so that Jonathan will not…try to self-medicate with other substances.” (127) She feels sure that Jonathan “still feels the weight of stigma” because “stereotypes about people with mental illness are all around us.” (129) She gives him “a weekly medicine dispenser for the rest of his marijuana and encourages him to split it into days” as she orders a book that Jonathan requests entitled Tweak: Growing Up on Methamphetamines (131). She finds text messages from “his supplier” regarding “acid” with instructions as follows: “Get three pills. Take them all at the same time for a maximum high.” (133) Carr responds by taking Jonathan for acupuncture treatments to treat his “anxiety” (136).

Jonathan now receives “disability checks…retroactive” so has enough money to buy a car. (135). Lisa (his “current therapist”) thinks a road trip to Merced “is a great opportunity for him to be more independent.” Carr gives him sixty dollars and “some healthy foods” reminding him to “call [her] in the evening to let [her] know he has arrived [in Merced]. He doesn’t.” (141) When she finally hears from him, he has “rear-ended a car and needs the insurance information.” (143) With the car impounded and Jonathan in jail for DUI, the parents pay the bail “by credit card.” (149) He comes home, and they move “Zoloft to the evening.” (152)

Carr sees that “under his untidy cascade of brown dreadlocks, his eyes shine contently” now; she finds him adorable (160). She is reading Dr. Elyn Saks’ book The Center Cannot Hold when Medi-Cal suggests she “become his legal guardian.” She loves “how forgiving [Jonathan] continues to be” (166).

While Tom goes to get “natural fertilizer” so they can “all dig [and] mix the fertilizer with the soil, and prepare the vegetable beds”, Carr finds her son dead in his room with a belt wrapped around his neck “attached to a cabinet doorknob.” (182) The coroner says that he probably died playing the “choking game” putting pressure on the neck arteries with a belt “in an attempt to get a short high.” Carr notes that “if Jonathan had been suicidal, [Dr. Ornish] would have noticed.” (186) Thus ends Part One.

Part 2: Love and Courage: Support for Helpers

The second part of the book documents Carr’s search for help. She draws from the broadest variety of sources (eg. psychological and medical as well as governmental experts, advocacy groups, support groups, and self-help books) to offer what she sees as encouragement to others “living with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses”.

Carr describes it as “gathering the wisdom of many sources.” She turns to NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) whose website defines mental illness as brain disorders that are biologically based. (39) She moves on to Michael Foster Green, professor of psychiatry and behavioral science, who believes “the solution is education.” (205) Carr is pleased that “psychiatrists widely acknowledge the importance of a person’s faith” but like those psychiatrists, her advice is unconcerned with the object of that faith (209).

She seeks to find “a healthy balance” as advised by Mental Illness Policy Org. She likes David Peters who compares “medication adjustments to trying on different pairs of shoes” (224) and courses on CBT that say “There is, once again, a balance.” (234) Carr concludes that mind-altering drugs “are not expressly mentioned in the Bible, and Christians have different opinions on the parallel between these substances and alcohol.” (238)

She is certain that “family members…have the inherent ability to create an environment conducive to healing” (242) and that “doctors and various medical professionals [are] blinded by their knowledge and jaded bureaucratic outlook.” (242) She then describes pastors and elders as “trained to help people in spiritual matters and may not understand important medical dimensions just as a doctor may not understand important spiritual dimensions” and concludes that “receiving both types of advice puts you in a stronger position to make a wise decision.”(245)

With balance as a priority, she makes no distinction between the advice of John Newton and that of a “medieval Jewish poet Yehuda Ha-Levi” (252) . She moves easily from David Sheff (Beautiful Boy) to “Rev. Stephen Donovan, pastor of congregational life at Escondido United Reformed Church, who has had much experience dealing with cases of mental illness.” (263) ) She looks to Judith Shulevitz, Ariel Okin, and Matthew Sleeth for help in turning the Sabbath into “A Prescription for a Healthier, Happier Life.” (278)

Conclusion

It is not uncommon today for people like Jonathan to be labeled as suffering from schizophrenia as opposed to the more accurate label of psychosis resulting from drug abuse. Schizophrenia as a diagnosis usually provides better insurance coverage and greater social acceptability. It is generally assumed that the term ‘schizophrenia’ refers to an actual disease entity (like cancer) that has a rational treatment and that its treatment is based on an accurate understanding of the underlying physiology (ie. chemical imbalance). Neither of these claims is true.

Cancer is diagnosed and treated according to lab tests (biopsies, blood tests) and/or imaging (CT, PET scans); schizophrenia is diagnosed solely on the basis of symptoms. It is simply a label given to people who appear to have bizarre thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Most psychiatric diagnoses codified in the DSM-V lack any scientific validity as disease entities.

Carr is an experienced and graceful writer. Because of this and because so-called mental illness is increasing exponentially (as would be expected considering its vague and expanding definition), this book will be popular. Christian theology is clearly not the base for Simonetta Carr’s advice. When Scripture is mentioned, it is used to comfort the author rather than to function as a source of strength and direction by which to deal rightly with the situation.

Her gathering of wisdom from many sources would surely cause true Wisdom to “cry aloud in the streets.” It would appear that Carr “did not choose the fear of the Lord” and had her “fill of [her] own devices” such that her book describes “fools who hate knowledge” (Proverbs 1:20-33). She repeatedly emphasizes natural fertilizer, natural grains, healthy food, etc. ignoring the clear message of Scripture that nature is cursed. “Cursed is the ground because of you” (Genesis 3:17). “The creation was subjected to futility” (Romans 8:20). Carr becomes like the “women weeping for Tammuz” (Ezekiel 8:14) and “baking cakes for the Queen of Heaven” (Jeremiah 7:18 and 44:15-18). She writes more like a member of a fertility cult than a woman of Christ.

Michael Horton says the book is “a treasure of truth, wisdom, and practical advice” and that “we need to think of mental illness like cancer.” (10, 11) His Forward claims that “she teaches us how to…” (11); while Carr claims, “This is not a ‘how-to’ book.” (13, italics mine) Both ignore the warning of I Timothy 6:20 regarding “the irreverent babble and contradictions of what is falsely called knowledge (science).”

Carr promotes Buddhist doctrine with the frequent repeating of the need for balance (“As in everything, we need to find a balance.)” (274) The book ignores God’s warning to Belchazzar: “You have been weighed in the balance and found wanting.” (Daniel 5:27). This is the only balance that should concern those born in the line of Adam.

The only answer to the infinite imbalance was provided on Calvary long ago and is not present in the comments by Christian leaders. These begin with a claim from Jonathan Aitken that Broken Pieces “is an essential resource and guide for anyone living with or around schizophrenia”. Though expected from David Murray and Richard Winter, it is especially sad to see Carl Trueman claim that “the church has historically not understood mental illness…that is thankfully changing.”

The change is a movement away from the rock toward the sand of sorcery (pharmakeia), and that shifting sand permeates Broken Pieces.

Far more solid than this book is the simple poetry written long ago:

“The heavier the cross, the heartier the prayer,

The bruised herbs most fragrant are.

If sky and wind were always fair,

The sailor would not watch the star.

And David’s Psalms had ne’er been sung

If grief his heart had never wrung.”

(verse 13 of a German hymn in Spurgeon’s Commentary on Psalm 69)