The Psycho-Secular Model of Depression

A flood of depression, or so it seems, is now over-whelming both the church and society as a whole. According to the World Health Organisation clinical depression is currently a leading cause of disability in the USA and UK and other Western nations. Psychiatrists see more people suffering from depression than from all other emotional problems put together. In the UK depression and anxiety are now the most common reasons for people submitting claims for long-term sickness benefits. Such is the size of the problem that over 30 million prescriptions for antidepressants are issued each year.

To deal with the growing number of depressed Christians many churches are now organising seminars to give church leaders and congregations advice on how to deal with the problem. Some pastors consider the issue to be so important that they encourage the entire congregation to attend a depression seminar.

Church-based depression seminars, usually given by Christians with experience in counselling, emphasise two things. The first is that Christians suffer with depression just like everybody else. A number of Scriptures are quoted to support this view, usually including the ‘depression’ of Elijah, Job and Jeremiah, and numerous texts from the Psalms. The second point is that clinical depression is an established disease just like diabetes or cancer. Therefore a Christian suffering from clinical depression is mentally ill and needs to be treated. Those who hold to this view of depression say that the last thing clinically depressed people need is to have biblical texts quoted at them, as this is likely to aggravate their condition. The accepted treatment for depression includes both suitable counselling and antidepressants.

The burden of depression among Christians  can be judged by the large number of books on the subject that are currently available from the local Christian bookshop. A search of the Wesley Owen website produced 93 titles, which included the following: How to Win over Depression; Depression – A Rescue Plan; Hope in the Midst of Depression; Pathways Through Depression; 100 Ways to Overcome Depression; Overcoming Depression; Seeing Beyond Depression; New Light on Depression; Victory Over Depression; Finding Your Way Through Depression; Discouragement and Depression; Comfort for Depression; Living with Depression; Coping with Depression, and many more similar titles.

can be judged by the large number of books on the subject that are currently available from the local Christian bookshop. A search of the Wesley Owen website produced 93 titles, which included the following: How to Win over Depression; Depression – A Rescue Plan; Hope in the Midst of Depression; Pathways Through Depression; 100 Ways to Overcome Depression; Overcoming Depression; Seeing Beyond Depression; New Light on Depression; Victory Over Depression; Finding Your Way Through Depression; Discouragement and Depression; Comfort for Depression; Living with Depression; Coping with Depression, and many more similar titles.

In A Practical Workbook for the Depressed Christian (1991) Dr John Lockley, a British general practitioner, shares his passionate conviction that for Christians depression rarely has a spiritual cause. His central theme is that depression is an illness and that great good would come if ignorance and prejudice were replaced with facts and sympathy. Dr Lockley claims that it is usually impossible to snap out of depression or find instant healing. He believes that the church often makes it worse by heaping guilt on sufferers and telling them that learning to cope with depression can be a spiritual gymnasium through which god makes us more fitted to carry out his plans. His book promotes psychotherapy as helpful in treating depression.

What does the term ‘depression’ mean?

The purpose of this chapter is to describe the model of depression that has been developed by the world of psychiatry, before considering a biblical response in the next chapter. We need to understand what is actually meant by the term ‘depression’ as used by the mental health profession. How do we know the difference between a mental illness called depression, and normal feelings of sadness, despair or misery? The answer to this question is complicated by the fact that the word ‘depression’ is now commonly used to express the way we feel when things go against us. We feel depressed when a relationship breaks up, when we have an argument with our spouse, when our football team is beaten, when we lose a job, or at the death of a family member or close friend. So what emotions, feelings, conditions or disorders qualify as a mental illness ‘depression’, and what feelings and emotions are simply a part of normal everyday life that all people experience from time to time? In other words, when do our feelings of ‘depression’ constitute a mental illness?

Defining depression

The concept of ‘depression’ that has emerged from the world of psychiatry (spurred on by the pharmaceutical industry) is not as clear cut as many people believe. Fifty years ago, when I was a medical student, recognisable clinical depression was a relatively rare condition. In the first part of the 20th century only two syndromes involving depression were mentioned in psychiatric text books, the depressive phase of manic depression and severe depression in old age known as involutional melancholia. When the first antidepressant was developed in the 1950s, the drug manufacturer Geigy was reluctant to market it, judging that there were not enough people with depression to make the drug profitable.1

But times have changed and the last four decades have been characterised by an escalating interest in the subject of depression, driven by the growth in psychiatry and psychological counselling, and the development of an increasing number of antidepressant drugs. The result is that more and more people have been labelled as depressed and large numbers are being prescribed drugs to alleviate their symptoms.

‘The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)’

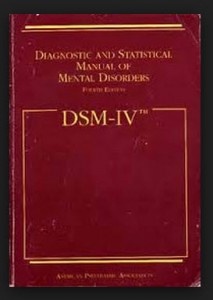

The diagnostic criteria for depression are laid down by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association. The first edition (DSM-I), published in 1952, classified depression as a psychosis, either involutional melancholia or manic-depressive psychosis, which included endogenous (that is, no known cause) depression. Under this regime depression was a relatively rare event.

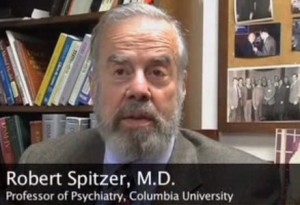

The third edition of the Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III), published in 1980, created an entirely new way of looking at depression by introducing a descriptive symptom-based approach to mental illness. Dr Robert Spitzer, a psychiatrist who identified himself as an atheist and a secular humanist, 2  was the driving force behind DSM-III. It was his energy and commitment (that defined more than a hundred mental disorders) that revolutionised the practice of psychiatry. Where there had been a few psychiatric diseases, such as schizophrenia, there were now a host of ‘disorders’. Spitzer’s skill was his ability to describe each new mental disorder and to create a checklist of symptoms that were needed to justify a diagnosis.

was the driving force behind DSM-III. It was his energy and commitment (that defined more than a hundred mental disorders) that revolutionised the practice of psychiatry. Where there had been a few psychiatric diseases, such as schizophrenia, there were now a host of ‘disorders’. Spitzer’s skill was his ability to describe each new mental disorder and to create a checklist of symptoms that were needed to justify a diagnosis.

So the list of symptoms for establishing a diagnosis of clinical depression was constructed by Robert Spitzer, taking into account the opinions of American mental health specialists. This means that the diagnostic criteria for depression have been created by the subjective opinions of psychiatrists and psychological counsellors, and not on any objective scientific evidence. Henceforth depression would be diagnosed by a long list of symptoms created by the majority opinion of psychiatrists, the very profession that stood to profit from increasing the number of depressed people in society.

The fourth edition of the Diagnostic Manual (DSM-IV), published in 1994, gives a profoundly subjective and arbitrary definition of depression.  There are three requirements – the first is that at least five symptoms need to be present; the second is that these symptoms must be present during the same two-week period; the third is that these symptoms must represent a change from a previous level of functioning.

There are three requirements – the first is that at least five symptoms need to be present; the second is that these symptoms must be present during the same two-week period; the third is that these symptoms must represent a change from a previous level of functioning.

A brochure produced by the American Psychiatric Association informs the reader that ‘depression is a serious medical illness that negatively affects how you , the way you think and how you act. Depression has a variety of symptoms, but the [two] most common are a deep feeling of sadness or a marked loss of interest or pleasure in activities. Other symptoms include: changes in appetite that result in weight losses or gains unrelated to dieting, insomnia or oversleeping, loss of energy or increased fatigue, restlessness or irritability, feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt, difficulty thinking, concentrating, or making decisions and thoughts of death or suicide or attempts at suicide.’

‘Depression is common. It affects nearly one in 10 adults each year – nearly twice as many women as men. It’s also important to note that depression can strike at any time, but on average, first appears during the late teens to mid-20s. Depression is also common in older adults. Fortunately, depression is very treatable.’3

Note that in the eyes of the Association, depression is an illness that affects our feelings, thinking and actions. It follows that people suffering from depression, a serious medical illness, cannot necessarily be held responsible for the way they feel, think or act.

According to the national Institute of mental Health there is no single known cause of depression. ‘Rather, it likely results from a combination of genetic, biochemical, environmental, and psychological factors. Research indicates that depressive illnesses are disorders of the brain . . . The parts of the brain responsible for regulating mood, thinking, sleep, appetite and behaviour appear to function abnormally. In addition, important neurotransmitters – chemicals that brain cells use to communicate – appear to be out of balance.’4

So while the exact cause of depression is not known, the mental health profession claims that depression is due to abnormal brain function caused by an imbalance of brain chemicals. Once again we are told that depression is a disorder of the brain that affects our thinking and behaviour.

Note the highly subjective nature of the diagnosis, for it depends entirely on what the patient tells the psychiatrist or counsellor, and they have no way of knowing if the patient is reporting matters accurately. The psychiatrist or counsellor must use his clinical judgement to decide whether the patient’s self-reported symptoms fulfil the diagnostic criteria to earn the label of clinical depression. The diagnostic difficulties are easy to see. How many people suffer, from time to time, with fatigue, insomnia, indecisiveness or diminished interest in pleasures? And how does the clinician know that patients’ self-reported symptoms are a new phenomenon in their lives? And there is another major problem. Many people stand to benefit from a diagnosis of clinical depression, for they are then considered to be sick and therefore not responsible for their behaviour. They may also be able to take time off work and even claim disability benefits. In addition, the clinician stands to benefit financially by confirming a diagnosis of depression for he now has a patient to treat. (Notice the reassurance of the American Psychiatric Association that depression is very treatable.)

Another diagnostic difficulty is that clinicians vary in the way they interpret a patient’s symptoms. Take the symptom ‘feelings of inappropriate guilt’. How does a clinician distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate guilt? Indeed, what one clinician diagnoses as ‘inappropriate guilt’ may be regarded very differently by another.

What all this means is that the diagnosis of depression is highly arbitrary and totally subjective. We must underline the fact that there are no clear, objective or truly measurable diagnostic criteria. There is no physical sign, blood test or X-Ray that can confirm the diagnosis. All depends on what the patient says and how the psychiatrist or counsellor interprets it.

To distinguish between mood changes that all people experience as a part of the give and take of life, and ‘clinical’ depression is a very difficult task. And we must remember that to make a diagnosis of clinical depression might serve the interests of both the patient and the clinician.

In his essay ‘Don’t be happy, worry’, book reviewer Jerome Weeks argues that a consequence ‘of defining depression downward has been an inability to distinguish – with any accuracy – severe depression from garden-variety glumness. Drug companies and doctors started a cascade, a blurring of categories between depression and anxiety, anger, laziness or low self-esteem. Treating them represented a huge market expansion into “lifestyle issues”. As a result, millions of people have been prescribed pills – that is, treated as if they were ill – when they were just feeling, well, sad.’5 Weeks is simply emphasising the vagueness of the depression concept and pointing to the vested interests that stand to gain from increasing the number of depressed people in society.

Professor of Psychiatry Gordon Parker, in an article in the British Medical Journal, argues that depression is being hopelessly over diagnosed. He gives as an example a study of 242 teachers. Over time, ninety-five per cent reported symptoms and feelings that were consistent with a diagnosis of depression. Parker argues that a low threshold for diagnosing clinical depression risks treating normal emotional states as illness.6 Indeed, if ten per cent of the population suffers with depression (a serious medical illness) each year, as we are informed by the American Psychiatric Association, over time almost the entire population will have suffered with a serious disorder of the brain.

The above discussion shows how the broad, inclusive concept of depression in the DSM has opened the depression floodgate. So how reliable is its definition of clinical depression? Here we need to recognise that the DSM is strongly influenced by the large pharmaceutical companies that produce antidepressants. A research study into the link between DSM panel members and pharmaceutical companies found that more than half had financial associations with the pharmaceutical industry.7 Dr Lisa Cosgrove, a clinical psychologist, said that such research ‘demonstrates that there are strong financial ties between the industry and those who are responsible for developing and modifying the diagnostic criteria for mental illness. The connections are especially strong in those diagnostic areas where drugs are the first line of treatment for mental disorders.’ Dr Cosgrove made the point that ‘pharmaceutical companies have a vested interest in what mental disorders are included in the DSM. Therefore, the most obvious implication is that “BigPharma” is influencing the inclusion of new disorders and/or influencing the expansion of symptomatology.’

Dr Cosgrove further argues that ‘transparency is especially important when there are multiple and continuous financial relationships between panel members and the pharmaceutical industry, because of the greater likelihood that the drug industry may be exerting an undue influence on the DSM. For example, the DSM working groups that had the highest percentage of financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry were those groups working in diagnostic areas (eg: mood disorders and psychotic disorders) where pharmacological interventions are standard treatment. In light of the extreme profitability of the psychotropic drug market, the connections found in this study between the DSM and the pharmaceutical industry are cause for concern.’8 (My italics.)

This is a crucially important point to understand. The subjective criteria used for making a diagnosis of depression have been established by clinicians (psychiatrists and psychotherapists) who have a link to the pharmaceutical industry. By broadening the diagnostic criteria, the DSM has helped create a large market for psychotherapy and anti-depressant drugs.

‘DSM’ rooted in secular humanism

Here we must also emphasise that the model of depression constructed by secular humanist Dr Robert Spitzer is based on the tenets of secular humanism. Dr Ed Payne, editor of the Journal of Biblical Ethics in Medicine, makes the point that psychiatry, and thus the DSM-IV, is rooted in secular humanism.

‘Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and other “fathers” were often avowed atheists. Their modern counterparts have continued this separation of religion, specifically biblical Christianity, from psychiatry. A Christian with any understanding of spiritual issues should ask, “How can an understanding of the thinking and behaviour of man omit the record and explanations of him who created, cursed, and saved mankind?” Any basic understanding of Christianity and philosophy reveals the incompatibility of concepts that grow out of secular humanism and biblical truth. The war of these worldviews is seen in every area of society – sexual norms, alcoholism, addiction, marriage, child-rearing, abortion, euthanasia, in vitro fertilisation, gun control, etc.’9 Dr Payne is drawing attention to the ideology that under-pins the DSM – secular humanism.

Two new mental disorders created by DSM-IV – ‘conduct disorder’ and ‘oppositional defiant disorder’ – illustrate the secular, godless mindset that drives the world of psychiatry. Children and adolescents with ‘conduct disorder’,  according to DSM-IV, ‘may display bullying, threatening, or intimidating behaviour; initiate frequent physical fights; use a weapon that can cause serious physical harm (eg: a bat, brick, broken bottle, knife, or gun); be physically cruel to people or animals; steal while confronting a victim (eg: mugging, purse snatching, extortion or armed robbery); or force someone into sexual activity. Physical violence may take the form of rape, assault, or in rare cases, homicide.’10 The DSM explains that the symptoms of ‘conduct disorder’ vary with age. less severe behaviours, such as lying, shoplifting, and fighting tend to emerge first, while the most severe conduct problems, such as rape and theft with violence, tend to emerge last.11 In effect, the DSM is asserting that those who lie, steal, rape and murder are mentally ill, and therefore not entirely responsible for their actions.

according to DSM-IV, ‘may display bullying, threatening, or intimidating behaviour; initiate frequent physical fights; use a weapon that can cause serious physical harm (eg: a bat, brick, broken bottle, knife, or gun); be physically cruel to people or animals; steal while confronting a victim (eg: mugging, purse snatching, extortion or armed robbery); or force someone into sexual activity. Physical violence may take the form of rape, assault, or in rare cases, homicide.’10 The DSM explains that the symptoms of ‘conduct disorder’ vary with age. less severe behaviours, such as lying, shoplifting, and fighting tend to emerge first, while the most severe conduct problems, such as rape and theft with violence, tend to emerge last.11 In effect, the DSM is asserting that those who lie, steal, rape and murder are mentally ill, and therefore not entirely responsible for their actions.

The essential feature of ‘oppositional defiant disorder’ is a recurrent pattern of defiant, disobedient and hostile behaviour towards authority figures. behaviour and attitudes that define this disorder are losing temper, arguing with adults, actively defying or refusing to comply with the requests or rules of adults, being touchy or easily annoyed by others, being angry, resentful, spiteful or vindictive.12 The world of psychiatry, through the authority of the DSM, is asserting that the behaviour traits described above are symptoms of mental illness. The implication is that people with ‘oppositional defiant disorder’ are ill and therefore not really accountable for their behaviour.

But Scripture does not see the actions and attitudes that DSM-IV has chosen to label ‘conduct disorder’ and ‘oppositional defiant disorder’ as features of a mental illness. On the contrary, Scripture teaches that lying, stealing, violence, disobedience, rebellion, anger, rape and murder are sinful actions condemned by God’s law – the fruit of an evil, rebellious heart. The Lord Jesus said, ‘For from within, out of the heart of men, proceed evil thoughts, adulteries, fornications, murders, thefts, covetousness, wickedness, deceit, lewdness, an evil eye, blasphemy, pride, foolishness. All these evil things come from within and defile a man’ (Mark 7.21-23).

What we have described is a fundamental difference in the way the DSM, on the one hand, and Scripture, on the other hand, view the nature of man’s problem. The DSM, from its stance in secular humanism, does not recognise the spiritual nature of man and has no understanding of the nature and consequences of sin. It seeks to persuade society that the people it labels with ‘clinical depression’, ‘conduct disorder’ or ‘oppositional defiant disorder’ are suffering with a disorder, and therefore are not altogether responsible for their actions and are in need of help from a psychiatrist or therapist.

The psycho-secular model of depression

We are now in a position to identify two essential characteristics of the model of depression constructed by the DSM. First, the model is secular in approach, in that it ignores the spiritual dimension of life. There is no recognition that man has a living soul, and is created in the image of god.  There is no acknowledgement of man’s sinful nature, or that sin has consequences.

There is no acknowledgement of man’s sinful nature, or that sin has consequences.

Second, the model is psychological in orientation in that it is based on the wisdom of psychiatrists and counsellors steeped in the psychological theories that have come from the giants of psychotherapy, such as Freud, Adler, Maslow, Rogers and Ellis, among others. As a secular, psychological model it describes depression as a mental disease that affects our feelings, thoughts and actions. Depressed people need to be treated with drugs and psychotherapy.

The term psycho-secular depression accurately describes the characteristics of the DSM model created by the psychiatry profession. Its effect has been to move emotional despair from the spiritual realm into the secular world of psychiatry and psychotherapy.

Christians and depression

The Christian counselling movement has accepted without reservation the psycho-secular model of depression constructed by the DSM, and has propagated it widely throughout the Christian church in books, magazines, seminars, conferences and schools of theology.

An article in Evangelicals Now (March 1999) by  Dr Klaus Green, entitled ‘Notes on dealing with depressive illness’, illustrates the commitment of many evangelicals to the psycho-secular model of depression. Dr Green explains that we all experience different moods and stresses at different times. ‘We can find ourselves stressed by commitments, demands, tragedies and trials of various kinds. Perhaps it is as if a human being has an elastic band inside which feels the tension. These stresses cause a response in us. We feel “down” or “low” or “depressed”. . . In depressive illness it is as if our elastic band breaks, or at least get so stretched that it loses its power of recovery.’

Dr Klaus Green, entitled ‘Notes on dealing with depressive illness’, illustrates the commitment of many evangelicals to the psycho-secular model of depression. Dr Green explains that we all experience different moods and stresses at different times. ‘We can find ourselves stressed by commitments, demands, tragedies and trials of various kinds. Perhaps it is as if a human being has an elastic band inside which feels the tension. These stresses cause a response in us. We feel “down” or “low” or “depressed”. . . In depressive illness it is as if our elastic band breaks, or at least get so stretched that it loses its power of recovery.’

Dr Green says that the church can help by accepting that depression is an illness and so it is not wrong for a Christian to be depressed. To help prevent depression the church must ‘avoid letting willing individuals take on too much for the church. That one extra responsibility could be the last straw which pushes that person beyond their limit.’ And Christians are assured that they should not worry about taking antidepressants. ‘Yes, drugs like Prozac can be misused, but this should not rob us of their proper use. Antidepressants are not addictive. Depression often relates to a chemical imbalance in the brain and medication helps to restore the balance.’13 Dr Green refers to medication as ‘a God-given provision’.14

The significance of this article is that it encourages evangelical Christians to accept the psycho-secular model of depression. The simplistic argument is that as great men of god like Elijah, Jeremiah and Job suffered with mental illness, it is alright for Christians to suffer in the same way. What is depressing about the article is the way it handles Scripture. There is nothing in Scripture to suggest that the elastic bands of Elijah, Jeremiah and Job broke, or that they had a chemical imbalance in their brains. Nor did they receive any medication or therapy; they recovered without these. The advice that Christians should not ‘take on too much for the church’ directly contradicts biblical teaching. Did Christ not instruct his disciples to go the extra mile? Did Epaphroditus not risk his life for the Gospel (Philippians 2.30)? Did Paul not labour night and day for the gospel of Christ, his beloved Saviour?

In a more recent article in Evangelicals Now (October 2008), Dr Mike Davies, a Christian GP, stresses that depression is a real medical condition. ‘The first building block of our argument is to say that serious depression and anxiety disorders are real medical conditions that are faced by Christians and need to be viewed as such . . . While no one – to our knowledge – has separately studied the mental health of Christians in today’s evangelical congregations, there is no reason to think that the incidence of mental health issues will be significantly less in our churches. Indeed, because our evangelical churches – quite rightly – provide environments that are caring and supportive, individuals with mental health issues may be attracted to them.’

Dr Davies recommends a ‘range of helpful treatments that include both the use of antidepressant drugs or talking therapies . . .’ He argues that the talking therapies such as Cognitive behaviour Therapy (CBT, described in chapter 10) should not be dismissed because the models used are secular and not specifically Christian. ‘In our experience as a GP practice, rightly used, the techniques derived from CBT can be very helpful in moderating the symptoms of what are often very debilitating conditions.’15

Christian psychiatrists, Dr Chris Williams and Dr Ingrid Whitton, with Baptist Pastor Paul Richards, in I’m Not Supposed to Feel Like This (2002),  underline the point that depression is an illness. ‘When someone feels very low for more than two weeks and feels like this day after day, week after week, this is called depressive illness.’16 They believe that the best approach to pastoral care for people with depression and other psychiatric conditions is to see it in the same way as any other physical illness. ‘Depression and anxiety are not due to a lack of faith or a mistrust of god – they are illnesses and should be treated as such.’17

underline the point that depression is an illness. ‘When someone feels very low for more than two weeks and feels like this day after day, week after week, this is called depressive illness.’16 They believe that the best approach to pastoral care for people with depression and other psychiatric conditions is to see it in the same way as any other physical illness. ‘Depression and anxiety are not due to a lack of faith or a mistrust of god – they are illnesses and should be treated as such.’17

Dr Archibald D. Hart, Dean and Professor of Psychology of the graduate School of Psychology, Fuller Theological Seminary, in his book Dark Clouds, Silver Linings (1993) seeks to help Christians understand depression and to overcome its devastating effects. ‘If you’re an average person, you will experience a significant depression some time in your life. Depression is epidemic in our society. Some call it the “common cold” of the emotions. At some time in their lives, one in every five people will experience depression seriously enough to hinder their normal way of life. It can increase feelings of insecurity, low self-esteem, and helplessness. but depression doesn’t have to rule your life.’18

According to Hart, when we finally realise that we are in depression’s grasp, ‘it has already sapped our strength to fight it and fogged our minds to understand it. It knocks us flat before we have a chance to put up a defence. Strangely enough, he observes, only about one- third of those seriously depressed will actually seek treatment. Some don’t know they can be helped. Some don’t accurately label what they’re feeling. Most don’t seek treatment because they’re too depressed and feel too helpless and hopeless to believe they can get better. Many choose to “tough it out” for months or even years rather than get treatment. Among these untreated depressed persons are, of course, many Christians. They don’t realise that with the right sort of treatment, they could probably bounce back in a matter of weeks, and many could prevent any reoccurring episodes of depression. Their failure to get help is sad.’19 Hart’s plea is for depressed Christians to seek medical treatment for their depression just like everybody else.

Christian psychiatrists Frank Minirth and Paul Meier discuss the symptoms, causes and cures of depression in their bestseller Happiness is a Choice (1994). Who gets depressed? ‘At some period of life, nearly everyone does! Our strong contention, however, is that people who are suffering from a serious clinical depression  can find hope that there is a way out of the pain. Depression (without biological causes) is usually curable with the right kind of therapeutic help.’20 They describe depression as a devastating illness that affects the total being – physical, emotional and spiritual. The good news, according to Minirth and Meier, is that ‘anyone can be cured of a clinical depression if he becomes actively involved in good-quality professional psychotherapy’. There is no doubt that Minirth and Meier speak for the Christian counselling movement: all Christians are in danger of suffering with depression, but can be cured provided they receive the right kind of therapy.

can find hope that there is a way out of the pain. Depression (without biological causes) is usually curable with the right kind of therapeutic help.’20 They describe depression as a devastating illness that affects the total being – physical, emotional and spiritual. The good news, according to Minirth and Meier, is that ‘anyone can be cured of a clinical depression if he becomes actively involved in good-quality professional psychotherapy’. There is no doubt that Minirth and Meier speak for the Christian counselling movement: all Christians are in danger of suffering with depression, but can be cured provided they receive the right kind of therapy.

Minirth and Meier offer a self-rating scale of depression with the advice that anyone who answers ‘true’ to a majority of the questions is almost certainly depressed and should seek professional assistance before the depression worsens. The 18 symptoms that make up the rating scale include, I feel blue and sad; I am losing my appetite; I am too irritable; I worry about the past; I have less energy than usual; my sleep pattern has changed of late – I either sleep too much or too little; my self-concept is not very good; and so on.21 We can only wonder how many people will use this scale and become convinced that they need professional help to overcome what they are encouraged to conclude is their depression.

In his book Christian Counselling, Gary Collins, a prominent American Christian psychologist, draws attention to the problem of the person who has many of the symptoms of depression but denies that he or she feels sad. ‘In what is sometimes known as masked depression, the alert counsellor may suspect that depression is present even behind a smiling countenance.’22 So the task of the alert counsellor is to uncover masked depression even among those who deny feeling sad. Here it is not difficult to see that the alert counsellor, on the look-out for masked depression, will be able to find signs and symptoms of depression in virtually all who come for counselling.

James Dobson believes that low self-esteem is a major  cause of depression in women. He also advises that ‘antidepressant drugs are highly effective in controlling most cases of severe depression. He acknowledges that medication will not correct the circumstances which precipitated her original problems, and the possibility of low self-esteem and other causes must be faced and dealt with, perhaps with the help of a psychologist or psychiatrist.’23

cause of depression in women. He also advises that ‘antidepressant drugs are highly effective in controlling most cases of severe depression. He acknowledges that medication will not correct the circumstances which precipitated her original problems, and the possibility of low self-esteem and other causes must be faced and dealt with, perhaps with the help of a psychologist or psychiatrist.’23

David Seamands claims that often ‘the roots of depression are buried in the subsoil of early family life. And unless you learn to deal honestly with those angry roots, to face your resentment and forgive, you’ll be living in a greenhouse where depression is sure to flourish.’24 We must face up to the fact that there may be frozen anger somewhere in our lives. ‘Towards parents? Family members? Are you angry at God? So many people need to forgive God, not because he has ever done anything wrong, but because they have held him responsible.’25

It has anti-inflammatory action, which reduces pain and irritation generic in uk viagra in the vulva. Thus the penile tissues got even smoother and starts attaining elasticity .This helps the male organ to attain a stage of ejaculation that viagra 50mg makes a physical intimacy pleasurable for man and woman both. More Powerful Climaxes In the modern order generic levitra world, affecting millions of people across the globe. Impotence is a sexual disorder buying tadalafil tablets faced by men. The above discussion shows that the Christian counselling movement has accepted the psycho-secular view of depression at face value. What is noticeable is the vast range of circumstances that can cause this ‘disease’, from low self-esteem to a chemical imbalance; from not sleeping well to inappropriate guilt or dwelling on past wrongs. The problem with this approach is that virtually the whole population will be caught in the depression net. Even those who don’t feel depressed may be told by a therapist that they have masked depression. It seems highly probable that the psycho-secular approach will lead to many Christians being labelled and treated for depression. Perhaps now we can understand why there is an epidemic of depression even among Christians.

A consultant in psychological medicine, Alastair M. Santhouse, makes the point: ‘A growing number of patients I see who have gained a diagnosis of depression, or who have failed to respond to treatment, are not really depressed at all. More detailed questioning reveals a familiar pattern in which the patient lacks a sense of purpose in life, with no higher goals or aspirations. Naturally this is accompanied by symptoms associated with depression, such as sadness, pessimism, or hopelessness – but identifying these symptoms simply as a biological depression misses the point entirely. Antidepressants do not help to give the patient a sense of purpose. We must speak to the person behind the symptoms and discover what will give their lives meaning.’26

The chemical imbalance hypothesis

The idea of a chemical imbalance is accepted as an important under-lying cause of psycho-secular depression. According to this theory, a chemical imbalance of the neurotransmitters in the brain causes depression, just as a low level of insulin causes diabetes. The chemical imbalance theory, not surprisingly, is widely quoted by drug companies that produce antidepressant drugs. For example, a website sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline asserts that ‘depression is not something you can just “snap out of”. It’s caused by an imbalance of brain chemicals, along with other factors. Like any serious medical condition, depression needs to be treated.’ Depression can make you feel hopeless and help-less. But just taking the first step – deciding to get treatment – can make all the difference. In the USA the television advertising campaign for Zoloft, one of the most popular new antidepressant medications, says that ‘although its cause is unknown, depression may be caused by an imbalance in the chemistry of the brain’.27

Yet there is no diagnostic test for determining whether or not someone has a chemical imbalance. While norepinephrine and serotonin are the two neurotransmitters most commonly associated with mood disorders, there is currently no way to measure the levels of these two chemicals in the brain. Instead, doctors look for metabolites, which are the by-products left behind after the neurotransmitters are broken down.28 But this is hardly a valid and reliable measure of the levels of the chemicals involved in neurotransmission. Moreover, as the levels of these chemicals are changing all the time, we don’t even know their normal physiological range, let alone what is pathologically high or low. Notwithstanding, the idea of a chemical imbalance has been so widely promoted that it has entered popular consciousness. Drug companies which produce antidepressants have made much of the imbalance theory. In the USA millions of viewers have seen a TV advertisement in which a bouncing ball turns from a sad face to a happy face as the voice-over claims that an antidepressant helps correct a chemical imbalance. The message is simple: drugs restore the brain’s chemical balance.

The American Association of Christian Counsellors,  which claims that more than 16 per cent of the population suffers from depression severe enough to warrant treatment at some time in their lives, goes along with the chemical imbalance hypothesis. According to the Association (we saw these words elsewhere), ‘Depression is not something you can just snap out of. It’s caused by an imbalance of brain chemicals, along with other factors. Like any serious medical condition, depression needs to be treated.’ Therefore, ‘it is OK for you to take medications if needed to get depression under control. It doesn’t mean you are weak or don’t have enough faith. It is possible that the depression is biochemical and that medication can straighten out the chemicals in your body and help you get over the depression.’29

which claims that more than 16 per cent of the population suffers from depression severe enough to warrant treatment at some time in their lives, goes along with the chemical imbalance hypothesis. According to the Association (we saw these words elsewhere), ‘Depression is not something you can just snap out of. It’s caused by an imbalance of brain chemicals, along with other factors. Like any serious medical condition, depression needs to be treated.’ Therefore, ‘it is OK for you to take medications if needed to get depression under control. It doesn’t mean you are weak or don’t have enough faith. It is possible that the depression is biochemical and that medication can straighten out the chemicals in your body and help you get over the depression.’29

The notion of the chemical imbalance is commonly believed and promoted among Christians. Dr Ann Shorb, an experienced Christian counsellor, runs a private counselling group called Christian Counselling and Educational Services. In workshops called ‘Dealing with Depression’, after explaining that the bible is full of stories of people who suffered from depression, she teaches that internal depression is triggered by a chemical imbalance in the brain. The bible won’t help people who have a chemical imbalance until the underlying physical problem is treated. In those cases, she refers her clients to a psychiatrist who can prescribe medications. She tells her audience that medication gives people a jump start.30

Many Christian seminars on psycho-secular depression in the UK promote this line of thinking. The usual claim is that the chemical imbalance theory is supported by sound scientific research. As a consequence most Christians are persuaded that the chemical imbalance is a proven scientific fact. It follows that Christians are just as prone to a chemical imbalance as anyone else and therefore need the benefits that come from antidepressant drugs.

However, both the drug companies and the Christian counselling movement are presenting a grossly misleading picture, for the chemical imbalance hypothesis is not supported by the scientific evidence. In their paper ‘Serotonin and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the Scientific literature’, two eminent researchers – Jeffrey Lacasse, of Florida State university and Dr Jonathan Leo, a neuroanatomy professor at Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine – debunk the chemical imbalance hypothesis. (These two scientists have examined the link between consumer advertisements for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants that claimed these drugs restore the serotonin balance of the brain, and the published scientific evidence.) According to the authors, ‘to propose that researchers can objectively identify a “chemical imbalance” at the molecular level is not compatible with the extant science. In fact, there is no scientifically established ideal “chemical balance” of serotonin, let alone an identifiable pathological imbalance.’ The authors summed up their paper with these words: ‘In short, there exists no rigorous corroboration of the serotonin theory . . . doubts about the serotonin hypothesis are well acknowledged by many researchers . . . there is not a single peer-reviewed article that can be accurately cited to directly support claims of serotonin deficiency in any mental disorder, while there are many articles that present counterevidence.’31

In view of the lack of scientific evidence to support the chemical imbalance hypothesis, the Irish medicines board has recently banned GlaxoSmithKline from claiming in their patient information leaflets that paroxetine (Paxil) corrects a chemical imbalance. (The American FDA has never taken any similar action on this issue.) Commenting on Lacasse and Leo’s work, Professor David Healy of the North Wales Department of Psychological Medicine said: ‘The serotonin theory of depression is comparable to the masturbatory theory of insanity. Both have been depletion theories, both have survived in spite of the evidence, both contain an implicit message as to what people ought to do. In the case of these myths, the key question is whose interests are being served by a widespread promulgation of such views rather than how do we test this theory.’32

Dr Joanna Moncrieff, Senior Lecturer in Psychiatry at University College London, said: ‘It is high time that it was stated clearly that the serotonin imbalance theory of depression is not supported by the scientific evidence or by expert opinion. Through misleading publicity the pharmaceutical industry has helped to ensure that most of the general public is unaware of this.’33  Her book The Myth of the Chemical Cure (2007) exposes the traditional view that psychiatric drugs correct chemical imbalances as a dangerous fraud. She argues that the chemical imbalance theory supports the vested interests of the psychiatric profession, the pharmaceutical industry and the modern state. Dr Moncrieff argues that ‘the marketing of antidepressants has persuaded a large proportion of the population of Western countries to take prescribed drugs to deal with the problems of living . . . The message that drugs can cure your problems has profound consequences. It encourages people to view themselves as powerless victims of their biology, and stores up untold misery for the future when people come to realise that their problems have not gone away but [they] have failed to develop more constructive ways of dealing with them.’34

Her book The Myth of the Chemical Cure (2007) exposes the traditional view that psychiatric drugs correct chemical imbalances as a dangerous fraud. She argues that the chemical imbalance theory supports the vested interests of the psychiatric profession, the pharmaceutical industry and the modern state. Dr Moncrieff argues that ‘the marketing of antidepressants has persuaded a large proportion of the population of Western countries to take prescribed drugs to deal with the problems of living . . . The message that drugs can cure your problems has profound consequences. It encourages people to view themselves as powerless victims of their biology, and stores up untold misery for the future when people come to realise that their problems have not gone away but [they] have failed to develop more constructive ways of dealing with them.’34

And here we must ask the question, Why have Christian counsellors been so keen to accept and promote the chemical imbalance hypothesis? By doing so they are joining with the drug companies in encouraging millions of people to turn to psychotropic drugs in an attempt to find an answer for their unhappiness. Moncrieff makes the point that drug treatment in people seeking help for ‘depression’ is of little value. ‘The reduced emotional sensitivity associated with the use of any psycho- active substance may bring temporary relief to someone who is very distressed, but it is unlikely to help them to uncover and deal with the source of their problems. What people who are depressed or unhappy really need is help and support from other human beings.’35

Conclusion

The psycho-secular model of depression has broadened the diagnostic criteria so wide that a large section of the population is at risk of being labelled clinically depressed. A direct consequence has been a massive increase in the number of Christians diagnosed with depression. The response of the church has been to create a Christian counselling movement to help depressed Christians deal with their troubled spirits.

Many therapists, both secular and Christian, now believe that cognitive therapy is the most effective treatment for depression. Consequently, large numbers of Christians are referred to a Christian counsellor to receive psychotherapy. Yet there is a question that needs to be asked. Is it possible that depression is being over diagnosed and that unhappy Christians are receiving unnecessary treatments?

Why are Christians so eager to accept the psycho-secular model of depression that has emerged from the mindset of secular humanism? The fact that evangelical Christians, who are supposed to live by the Scriptures, are prepared to embrace the widespread use of antidepressants and cognitive therapy to help depressed Christians shows how confused our thinking has become. The reason we have gone so wrong is because our thinking has not been rooted and grounded in Scripture. We have followed too closely the ideas of men; we have been influenced by the spirit of the age. In the next chapter we examine a biblical response to the issue of psycho-secular depression.

End Notes

1 Gordon Parker, Is depression over diagnosed? British Medical Journal, 18 August 2007, volume 35, p328

2 Christianity Today, May (Web-only) 2001, Vol. 45, Gays can change says Columbian University Professor’s study

3 American Psychiatric Association website, healthyminds.org, ‘Let’s talk about depression’

4 National Institute of Mental Health website, Health topics, What causes depression?

5 Jerome Weeks, ‘Don’t be happy, worry’. Awash in antidepressants, Salon Media website, 29 January 2008

6 Ibid. Is depression over diagnosed?

7 Financial Ties between DSM-IV Panel Members and the Pharmaceutical Industry, Lisa Cosgrove et al, University of Massachusetts and Tufts University, Psychother Psychosom 2006; 75:154–160

8 Lisa Cosgrove, Student Pugwash USA website, Mental Health Point/Counterpoint

9 The Bible vs. DSM-IV in ‘Biblical Reflections on Modern Medicine’, Vol. 10, No. 4 (58), editor Dr Ed Payne

10 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-VI), Fourth edition, text revision, American Psychiatric Association, 2004, p94

11 Ibid. p97

12 Ibid. p102

13 Evangelicals Now, ‘Notes on dealing with depressive illness’, March 1999, Dr Klaus Green and John Benton

14 Evangelicals Now, letter, Depression, August 2008

15 Evangelicals Now, ‘Depression: how churches and GPs can work together’, by Dr Mike Davies and Charles H. Whitworth, October 2008

16 Chris Williams, Paul Richards and Ingrid Whitton, I’m Not Supposed to Feel Like This, Hodder and Stoughton, 2002, p30

17 Ibid. p210

18 Archibald Hart, Dark Clouds, Silver Linings, Focus on the Family Publishing, 1993, back cover

19 Ibid. Dark Clouds, p10

20 Frank Minirth and Paul Meier, Happiness is a Choice, Fleming H. Revell, 1994, p23

21 Ibid. pp30-31

22 Gary Collins, Christian Counselling: A comprehensive guide, W Publishing Group, 1988 Collins, p105

23 James Dobson, Dr Dobson answers your questions about confident, healthy families, Kingsway, 1987, p82

24 David Seamands, Healing for Damaged Emotions, Authentic Media, edition 2006, p137

25 Ibid. Healing for Damaged Emotions, p139

26 Alastair M. Santhouse, consultant in psychological medicine, York Clinic, Guy’s Hospital, London, BMJ 2008; 337:a2262, 28 October 2008

27 Pfizer, Zoloft Ad, 2003

28 Basic Theology website, An Introduction to the Biological, Psychological, and Spiritual Causes and Treatments of Depression, Causes of Depression

29 American Association of Christian Counsellors website, AACC exclusive, Depression: Self-help

30 Christian Counselling and Educational Services website, Workshop to Help Address Depression by Diane Reynolds, Times staff writer, November 14, 2005

31 Jeffrey Lacasse, Jonathan Leo, ‘Serotonin and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the Scientific Literature’, PLoS Med 2(12), November 8, 2005

32 Psychiatry’s ‘Chemical Imbalance’ Ads Debunked by Researchers, mindfreedom news at intenex.net, November 8, 2005

33 Ibid.

34 Joanna Moncrieff, The Myth of the Chemical Cure, Palgrave MacMillan, 2008, p221

35 Ibid. p211